Event Storming, created by Alberto Brandolini, is a flexible workshop format used to collaboratively explore complex business domains. It’s the most effective method we’ve seen for understanding business processes, solving problems, and agreeing on priorities. It naturally engages stakeholders and helps build alignment between different departments within an organization.

"A network of interdependent agents influencing each other" —Alberto Brandolini

In an organization, a complex domain arises when tasks are carried out in multiple steps, involving several teams or individuals. An example could be a recruitment process, where multiple stakeholders—HR, the hiring manager, team members, and security—must evaluate a candidate from different perspectives. The decision-making is collaborative, and success depends on factors like team fit, timing, communication, and adaptability.

Even with clear goals, the outcome is not entirely predictable, and each hiring situation may require a different approach to ensure effective onboarding and long-term success.

When a domain is complex, the real challenge in software projects is not writing code faster—it's understanding the domain or business processes more quickly. It's about identifying the right problem to solve.

While we have many tools to help us write software faster, there are still very few that help us understand the domain more effectively. This is where Event Storming comes to the rescue.

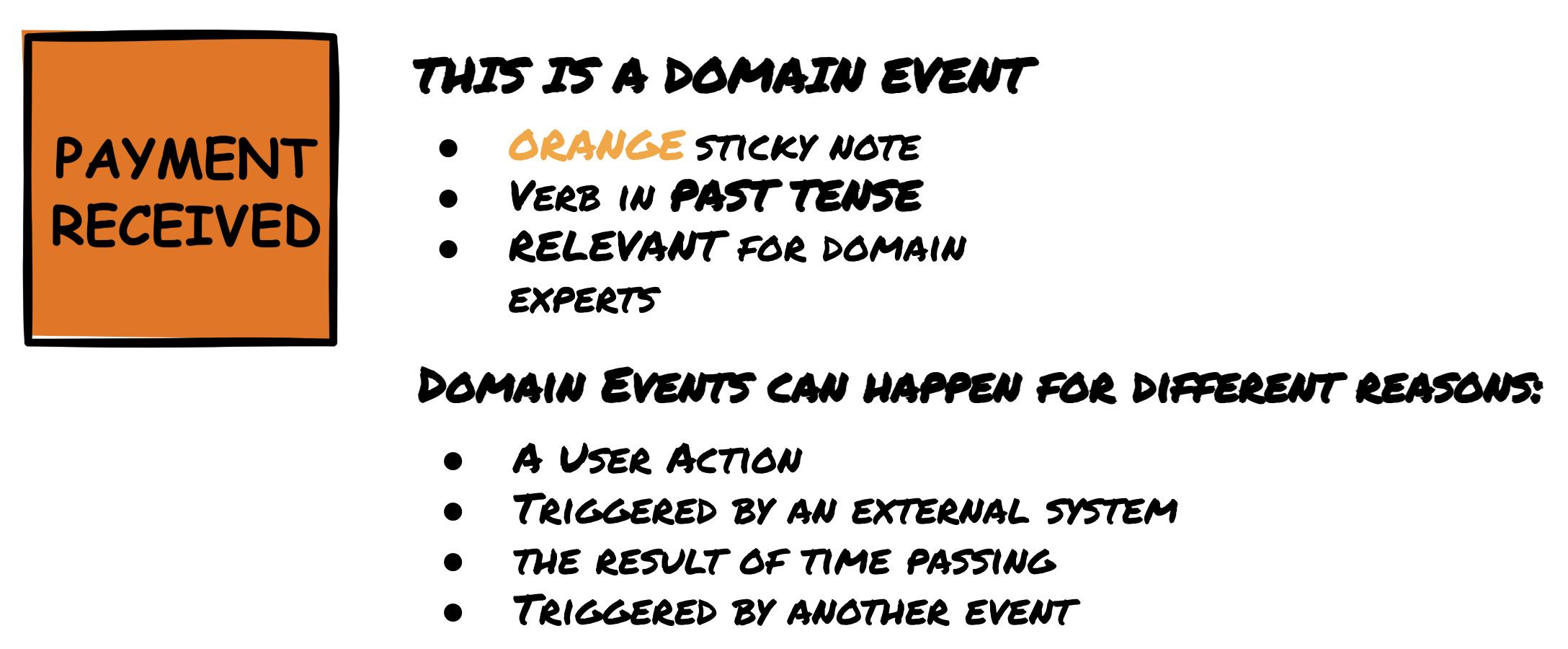

Event Storming uses a building block called a Domain Event. A Domain Event is something that happens and is relevant to the business or organization.

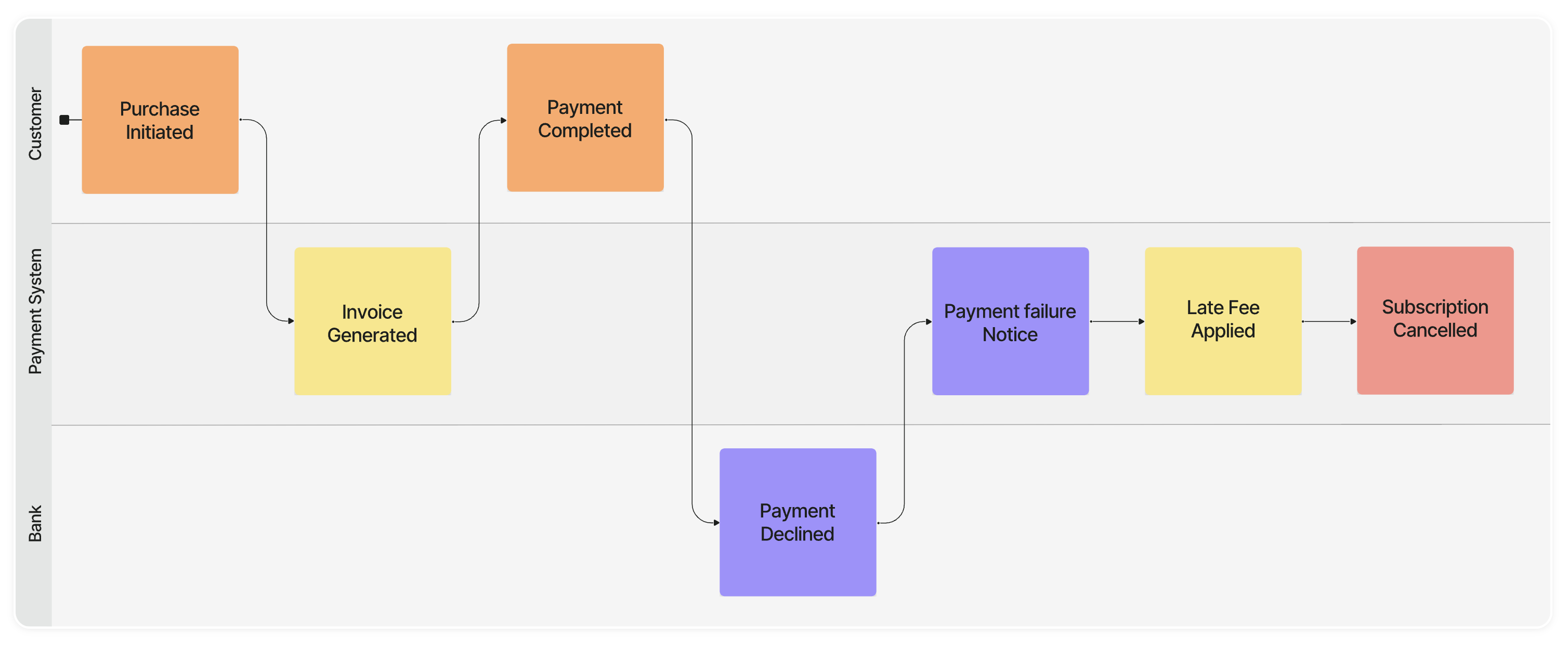

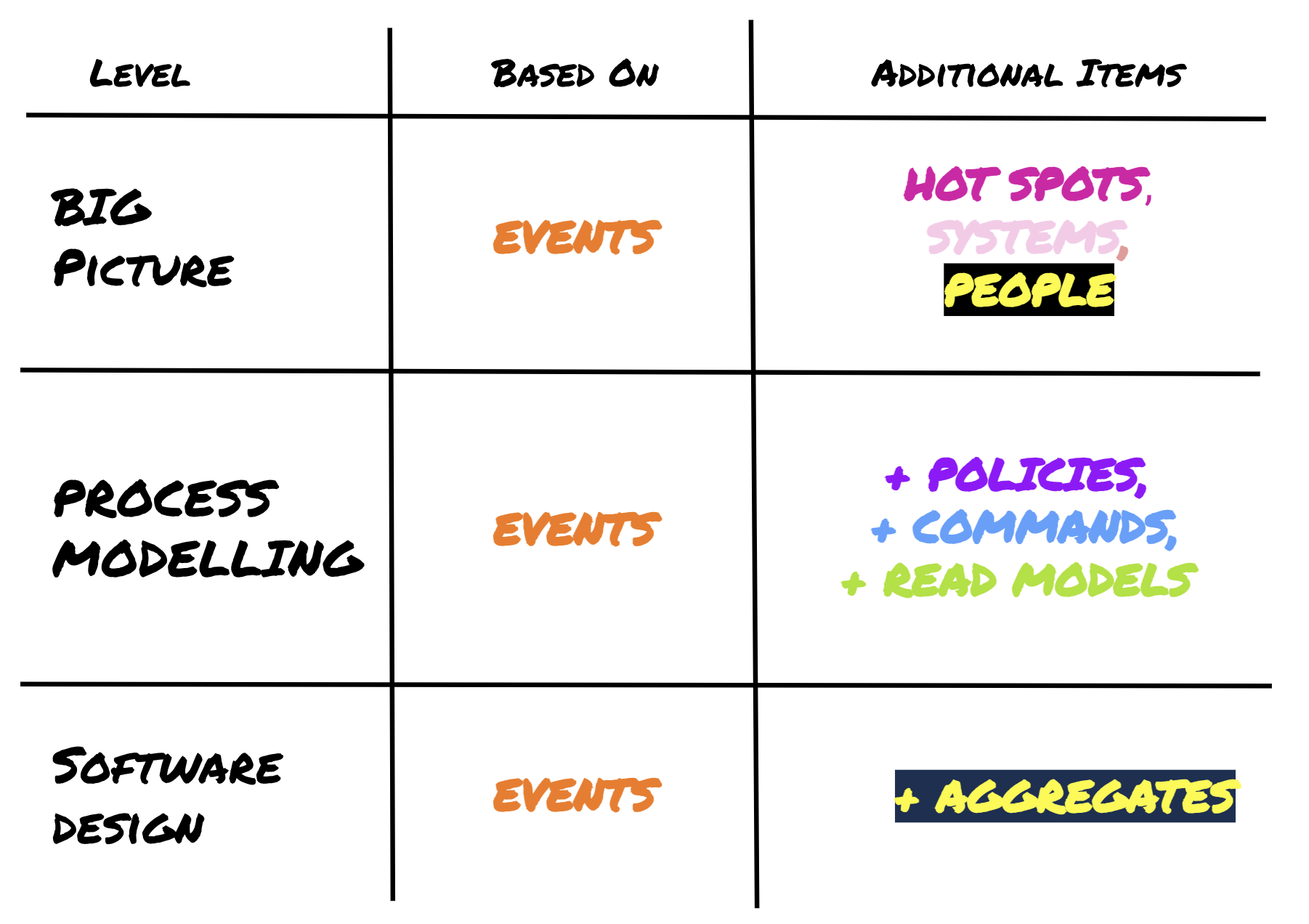

Event Storming can be done at different levels and for different purposes. The three most common variations are:

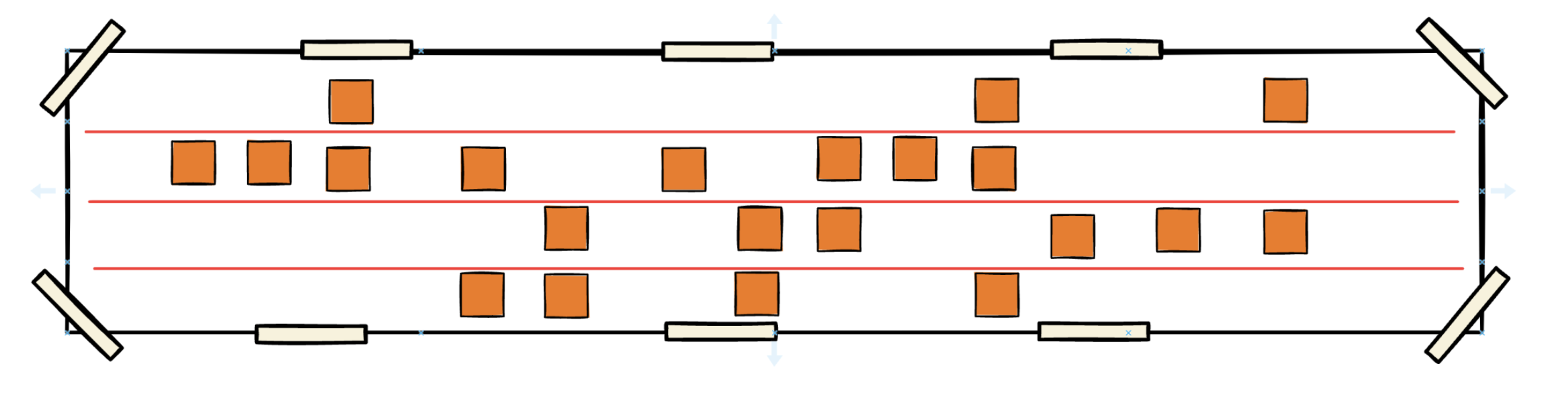

At all levels, Event Storming is based on Domain Events placed along a timeline, but each level introduces new kinds of elements into the notation:

The main purpose of Big Picture Event Storming is to maximize learning by collaboratively exploring a business domain. The goal is to create a shared understanding across departments or silos and to agree on which problems are most critical to solve. During the workshop, inconsistencies are automatically visualized. Example scenarios include:

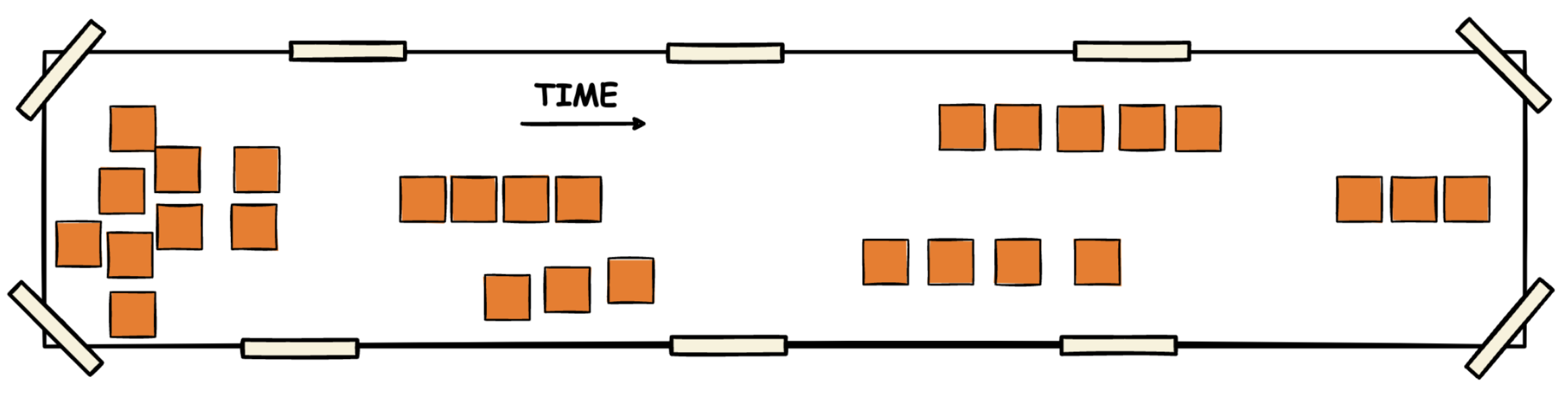

Domain Events are initially collected in mixed order through brainstorming but are eventually arranged on a timeline. As participants organize the events chronologically, they are encouraged to communicate—and often discover things they hadn't considered before. These conversations lead to valuable insights. Different perspectives are revealed.

If participants disagree at first, that’s actually a good sign—sometimes even preferable. Disagreement is better than silence.

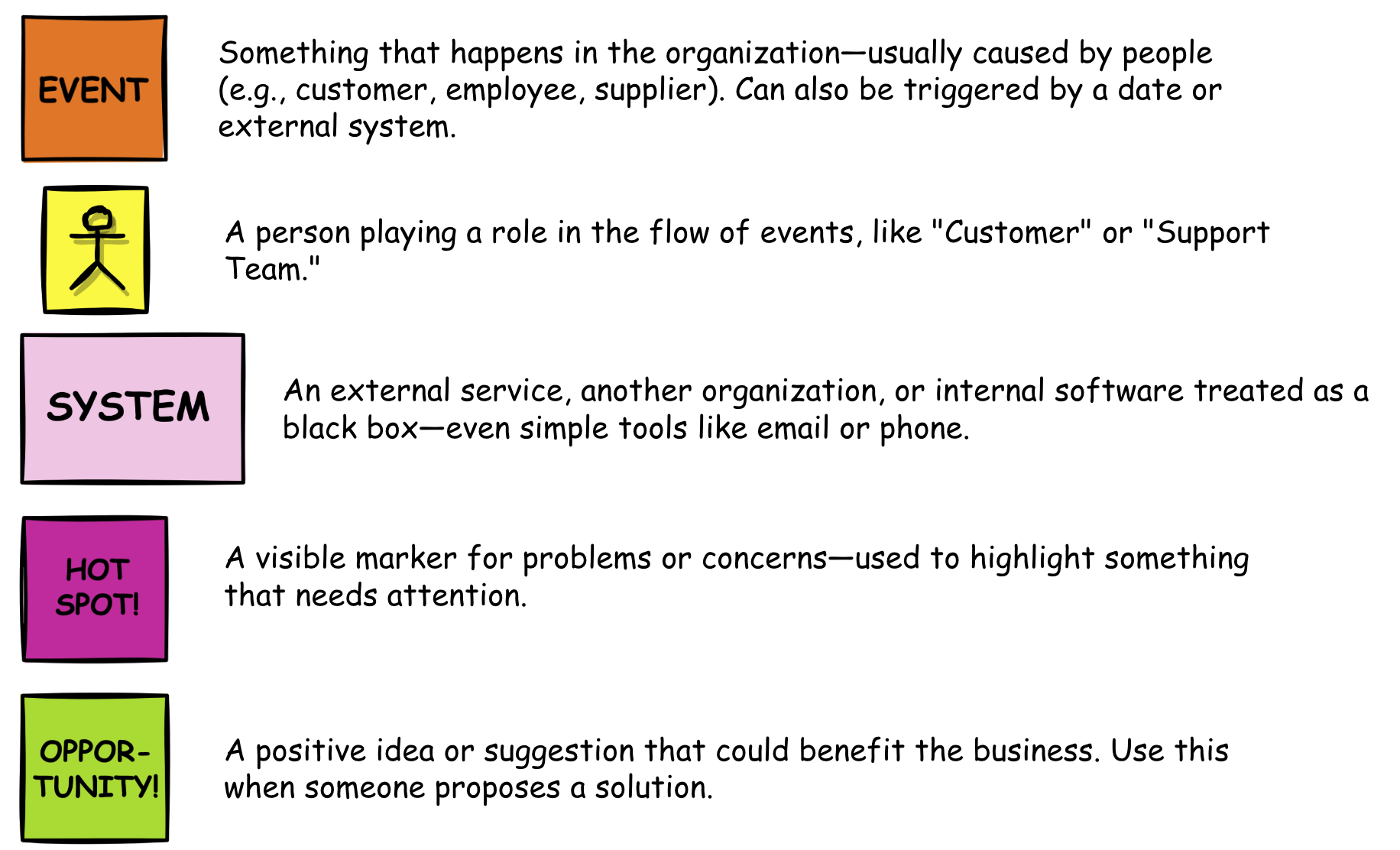

In Big Picture Event Storming, we commonly use a notation with five different colors. However, the workshop’s goal should always determine which notation to use. There is no best-practice notation that works in all situations—feel free to customize it to suit your needs. With experience, you’ll learn to make better and better choices.

So, you’ve been asked to facilitate a Big Picture Event Storming session—here’s how to prepare:

The room is ready and the participants are in—time to kick off the workshop. Here's an overview of the steps, followed by more detail on the key phases.

Start with a brief, informal round of introductions. Optionally, do a quick 20-minute warm-up on a familiar process, like recruitment or ordering a pizza.

Present the goals and align on the objectives. You might say something like:

“We’re going to explore the business process as a whole by placing relevant events along a timeline. We’ll highlight ideas, risks, and opportunities along the way.”

Keep the initial explanation of the method minimal. Instead, introduce concepts as they become relevant. Display a legend (notation guide) clearly on a whiteboard or paper and briefly walk through it before starting.

Now ask participants to write Domain Events on orange sticky notes and place them on the wall—all at the same time.

Give each person a stack of orange notes and a marker. Let them dive in. Warn them that this phase will feel chaotic, and that’s perfectly fine—structure will come later. It’s more effective to get moving quickly than to over-explain.

Help people get started if needed. Good general prompts include:

If someone hesitates, gently prompt them by asking about events relevant to their work. Your role is to help everyone get into the flow. Some people will start conversations; others may work quietly in parallel.

Timebox this phase to about 30 minutes, but adjust as needed based on the scope. Don’t worry about capturing every single event now—missing items can always be added later.

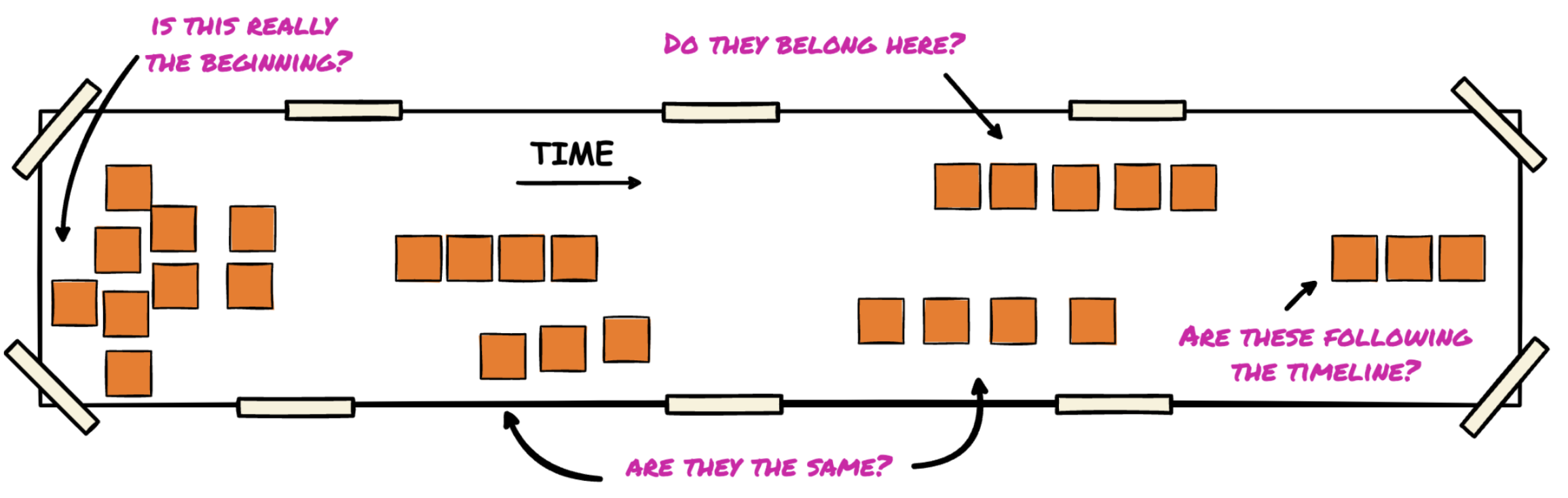

Now it’s time to get people collaborating by arranging all Domain Events on a single timeline from left to right.

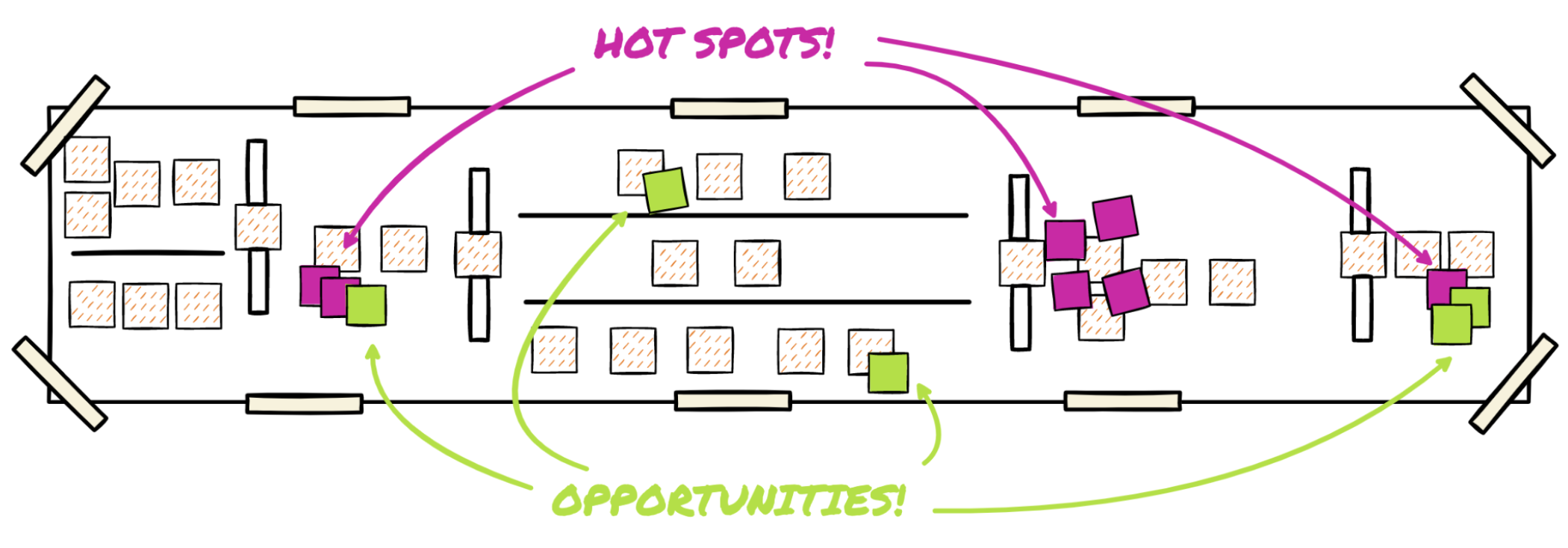

Some participants may have started their own separate timelines—now they must cooperate to align everything into one shared view. Encourage them to add missing events and start placing Hotspots (problems) and Opportunities (ideas or improvements) as they go.

Participants might ask: “Which event comes first?”

Answer: “We’re not aiming for perfection—just choose the most likely or preferred order.”

Arranging everything on one timeline can be messy. You may run out of space in some areas while others remain sparse. After a few minutes, you’ll likely need to step in and suggest a sorting strategy to guide the group. Useful strategies include:

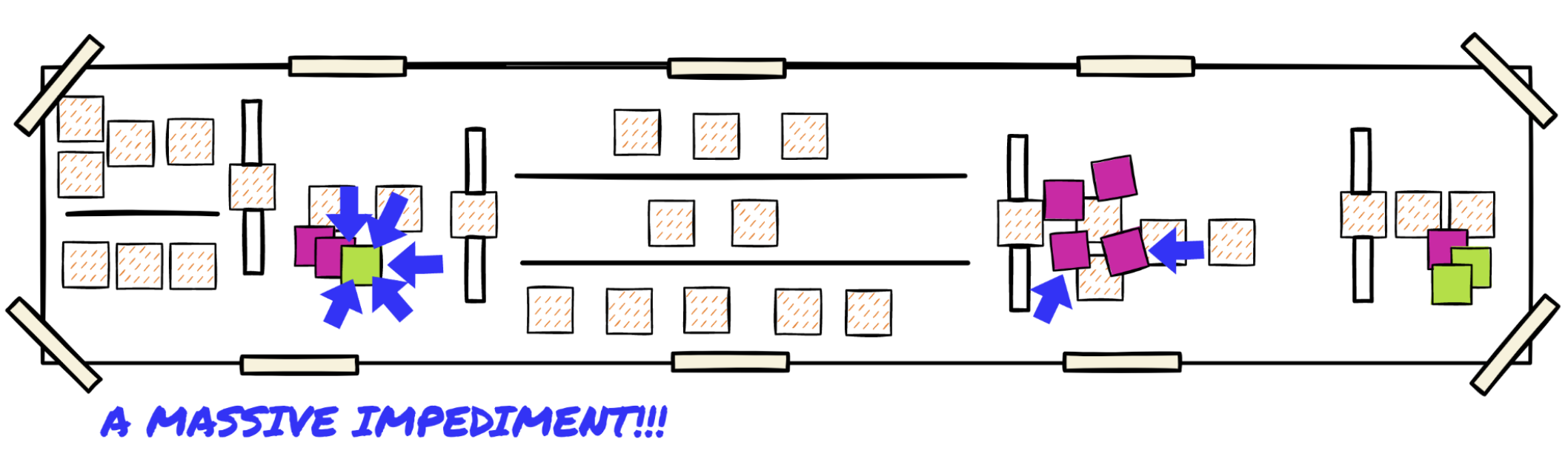

When disagreements or blockers arise, encourage participants to write a red Hotspot sticky note and place it at the problem area. This allows the group to move on and revisit all open issues together later.

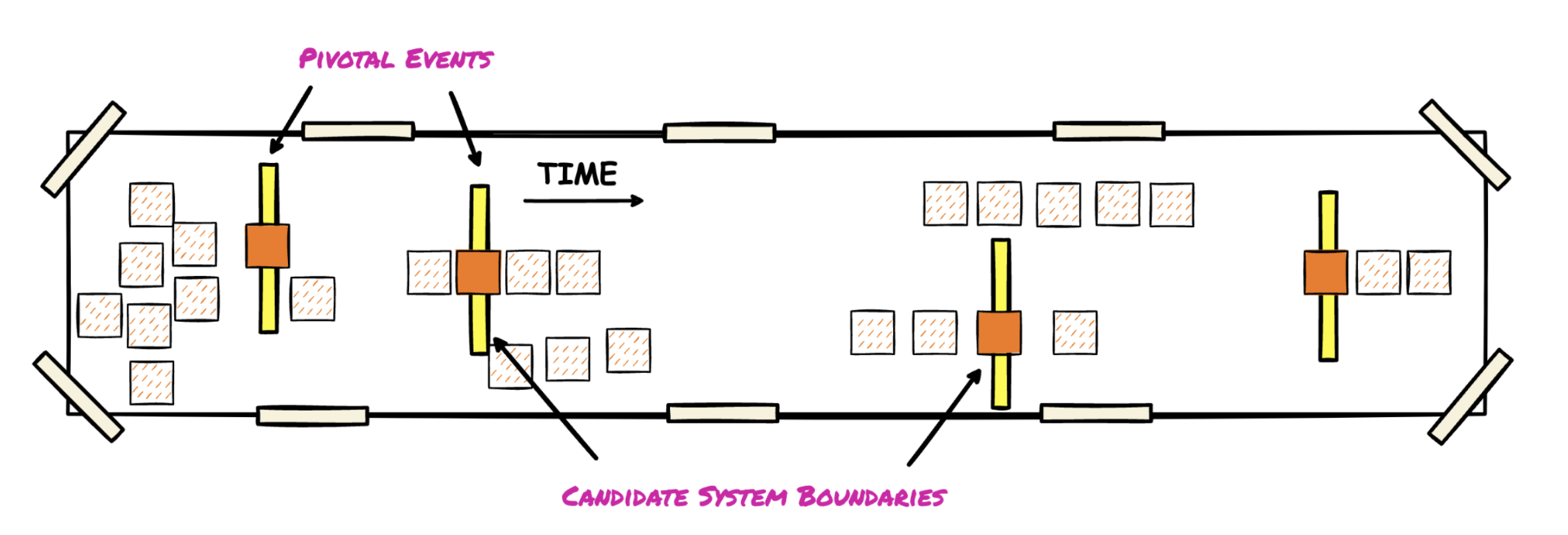

Identify key pivotal events and mark them—e.g., with a yellow strip of tape beneath each one. Ask participants to place all other events relative to these anchors in time.

Don’t overthink which events to pick—just choose ones that help distribute the flow across the wall. You can adjust them later as the structure evolves.

Look for events that are especially relevant to the business or mark a transition between phases.

Use a marker to draw swimlanes that separate roles, departments, or parallel processes. This makes the timeline easier to read and visually clear.

The trade-off: it takes up more space, so use it when clarity outweighs the need for wall real estate.

Most workshops naturally combine strategies. We often start with Pivotal Events, then add local Swimlanes where they help improve clarity.

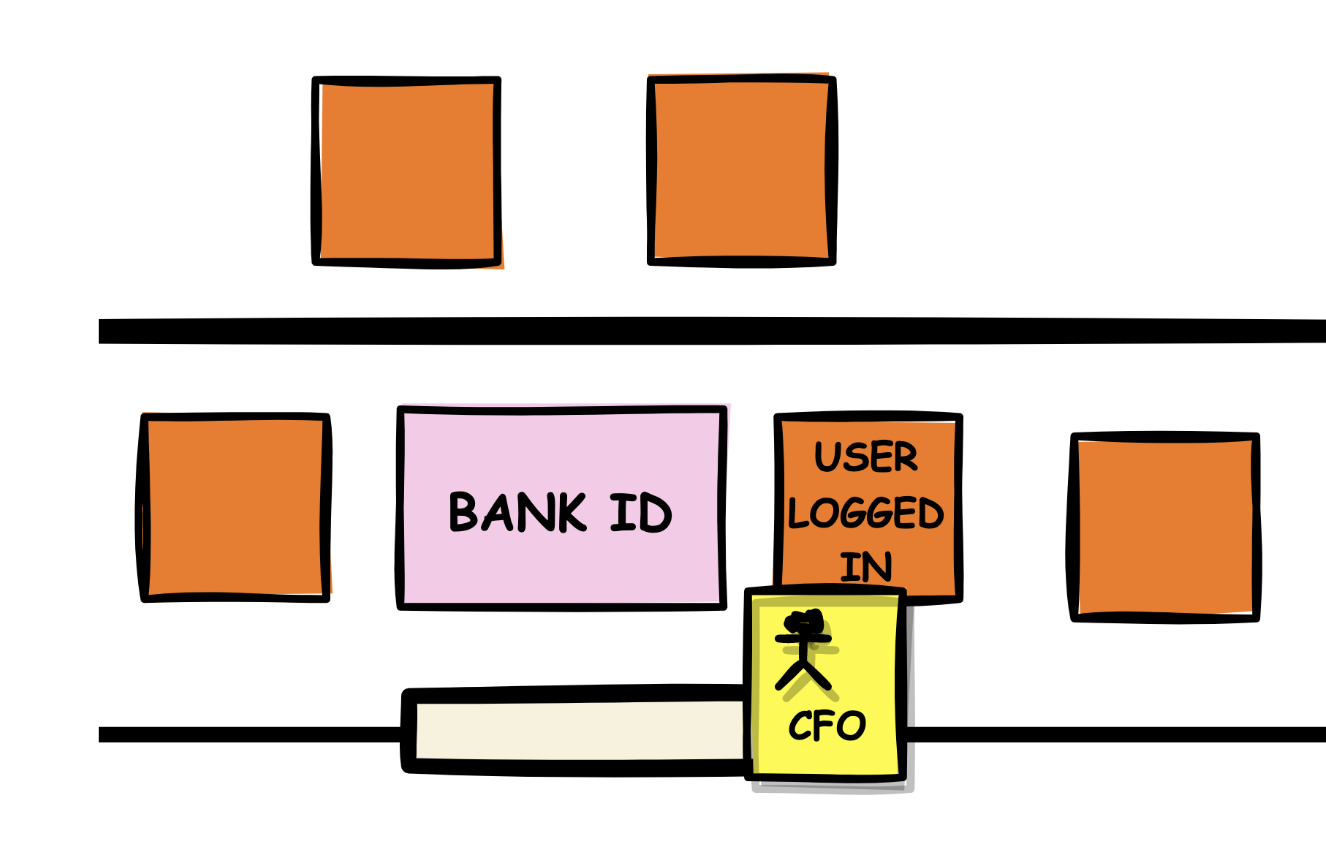

Who are the key roles and systems involved in the flow of events? In this step, we make them visible to better understand potential challenges.

Use small yellow stickies for people and large pink stickies for external systems. Place them on the modeling surface where they play a meaningful role.

This step often surfaces many Hotspots and comments.

However, this step is not always necessary—skip it if the issues are already clear, the system doesn’t exist yet, or everything is already well-known. Sometimes it’s enough to highlight only external dependencies.

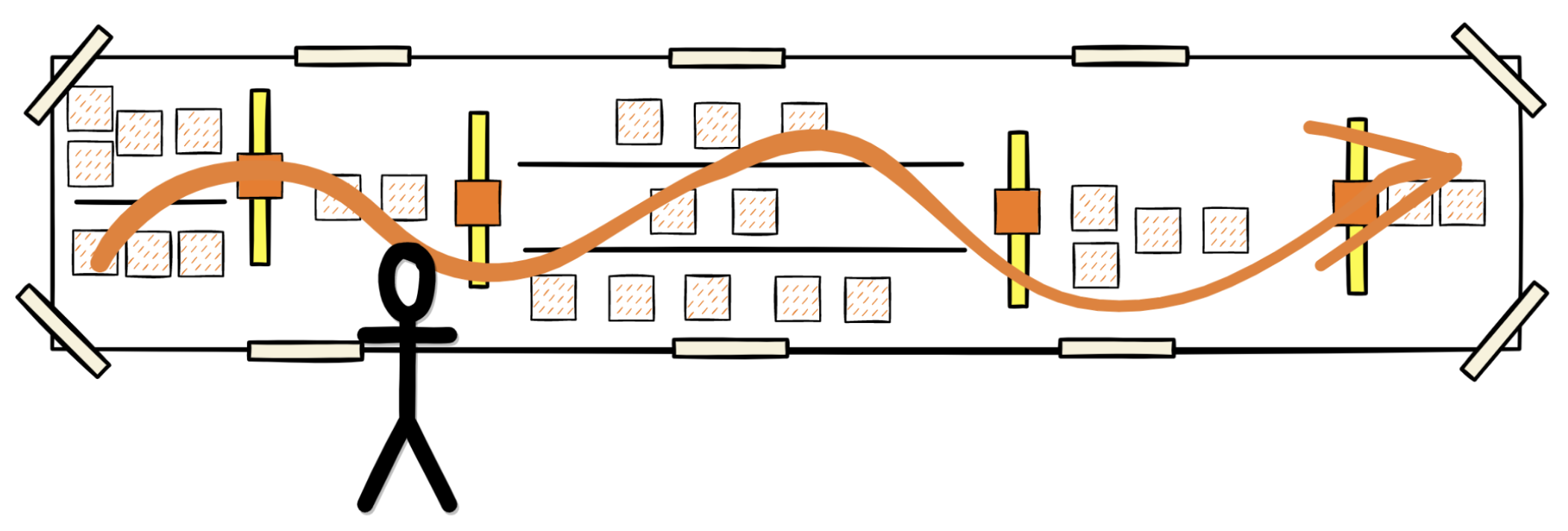

To ensure consistency, ask participants to take turns as narrators. Each person walks along the timeline and talks through the chain of events.

The rest of the group should challenge unclear parts, fill in gaps, and suggest improvements. Being the narrator is demanding, so keep turns short—around 5–10 minutes each.

Rearrange events, add missing ones, and place Hotspots or Opportunities as needed. Let the group assist the narrator in updating the board.

This step often takes the most time—a few hours is normal. Be sure to include refreshment breaks.

After the walkthrough, do a final pass in reverse—from end to start.

For example: for an invoice to be paid, it must first be sent. So, “Invoice Sent” should appear to the left of “Invoice Paid.”

This often reveals missing events. When that happens, pause and ask the group to help add them.

At the end, ask everyone: “Is anything still missing?” — and expect a few more additions.

Set aside dedicated time for participants to focus solely on identifying problems and opportunities.

Even if some Hotspots and Opportunities have already emerged earlier, this is the moment to dig deeper—to surface any lingering frustration, inefficiencies, or great ideas that haven’t yet been expressed.

Give the group 10–15 minutes to reflect and add notes.

One of the most impactful parts of Big Picture Event Storming.

Give each participant 2–3 arrow votes—a large black arrow drawn on a blue sticky note. Say something like:

“Everything we’ve captured is important, but now it’s time to pick the two most urgent problems or opportunities you believe we should focus on.”

Voting only makes sense once everything is visible. Sometimes there’s clear consensus; other times, the results are surprising. Either way, the outcome is visual and powerful.

A good session is a learning experience across silos—participants often gain new insights into their own organization. Usually, a few top issues or opportunities stand out just by glancing at the wall.

Sometimes the key outcomes are already reached by the end of the session:

everyone has a deeper understanding of the domain, and the top problems or opportunities have been clearly identified and agreed on.

For many organizations, simply acting on the top 2–3 issues can lead to a noticeable performance boost. In some cases, those few sticky notes are all the documentation you need.

Other times, you’ll want to document everything and continue with Process Modeling or Software Design in a follow-up session.

Either way, take photos of the board so the insights are preserved and can be revisited later.

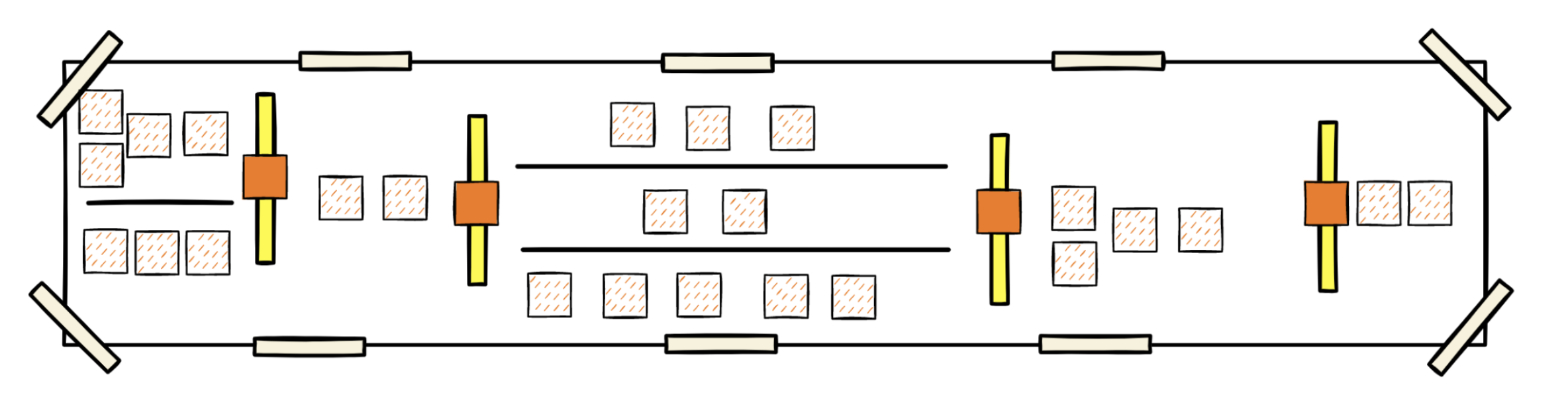

Process Modeling Event Storming shifts the focus from a high-level exploration to the detailed design of a specific business process. Unlike the broad, exploratory nature of a Big Picture workshop, this phase is characterized by its focus and constraints. The team, typically a smaller group of 4-8 people, zooms in on a single, end-to-end process with an agreed-upon starting point and a clear goal. This can be a process identified as a key area during a Big Picture session or one being designed entirely from scratch.

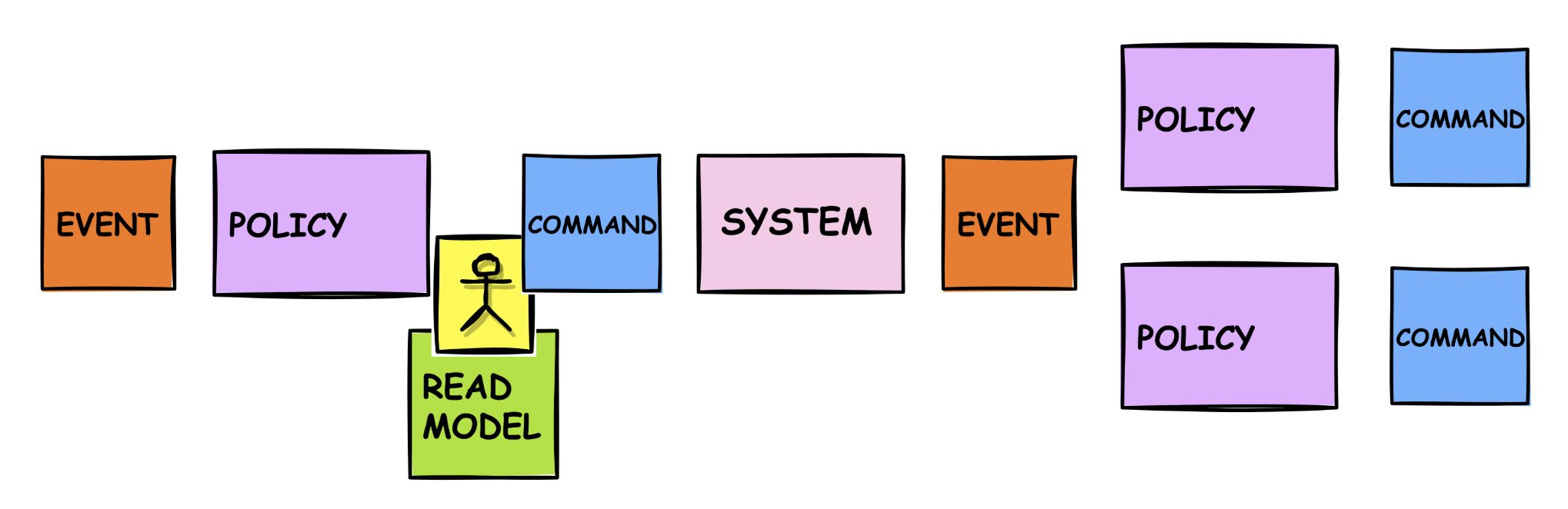

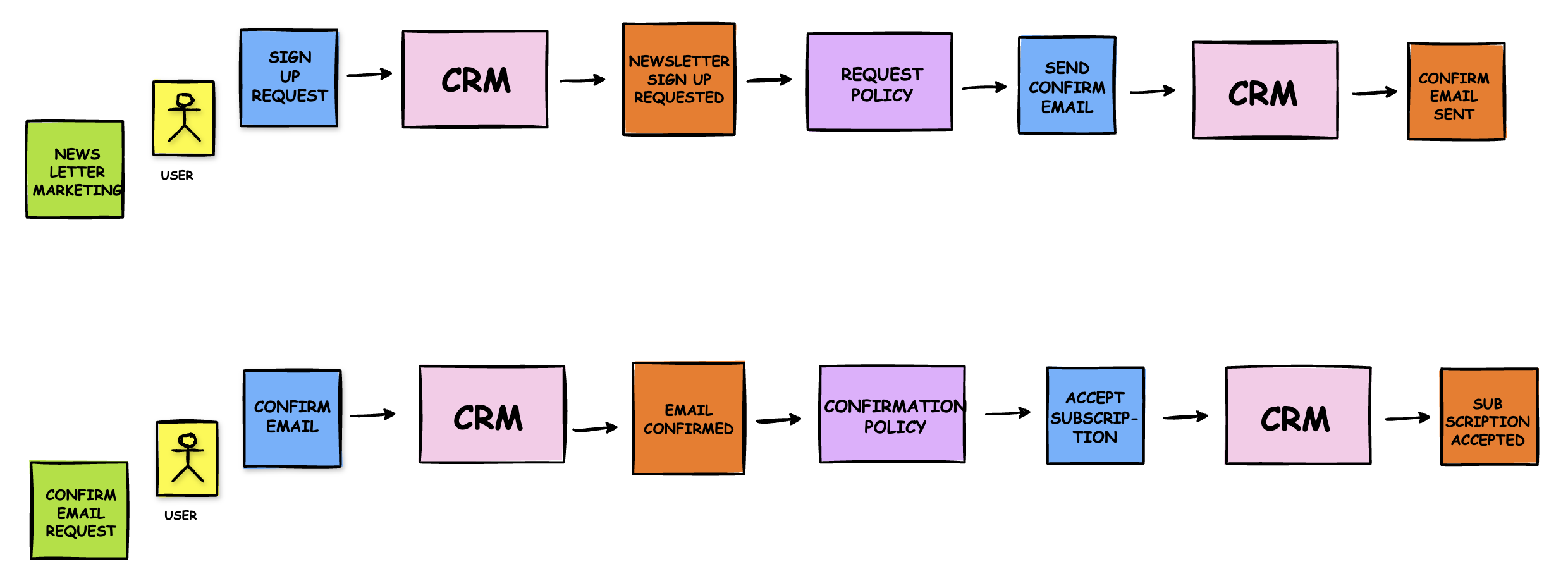

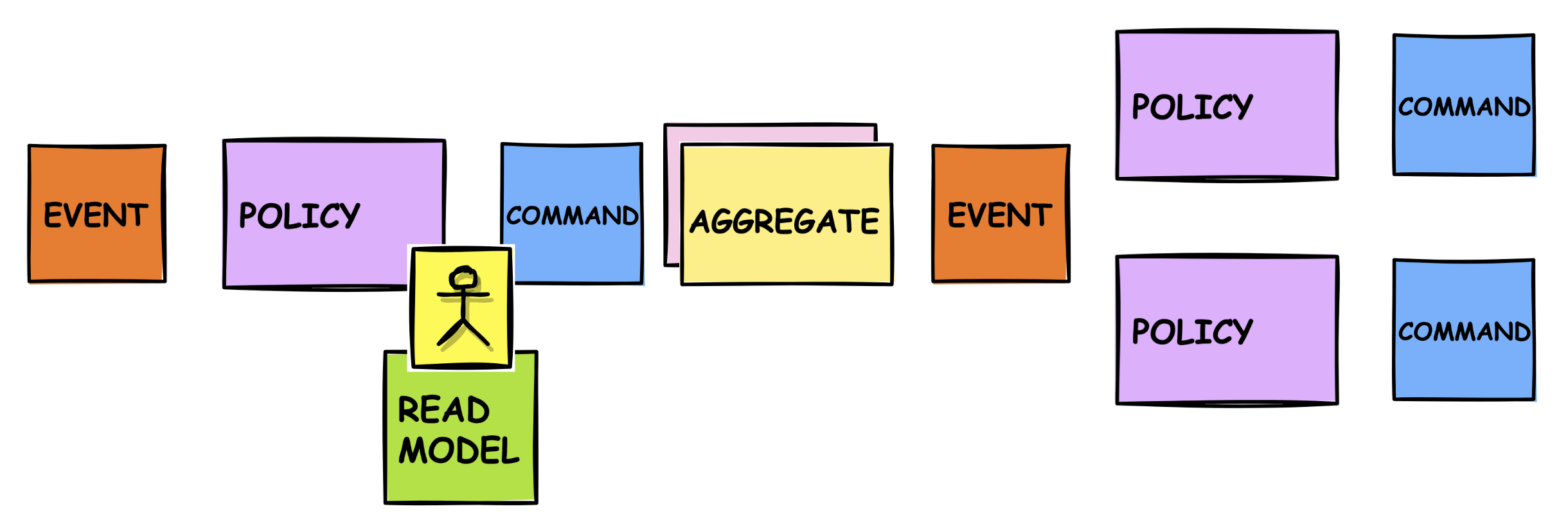

The collaboration style also differs significantly. Instead of many participants working in parallel, the team works together, sequentially mapping out the process one step at a time. The typical workflow is as follows:

This structured approach ensures the team develops a deep, shared understanding and can effectively design a robust solution.

Process Modeling builds on the Big Picture notation with three additional elements:

![A legend titled 'Additional Notation Used in Process Modeling' explaining three types of sticky notes used in EventStorming: Purple note labeled 'POLICY': A business reaction to an event, typically framed as 'Whenever [Event], then [Command].' Green note labeled 'READ MODEL': Represents the information needed to make a decision, such as price or stock availability. Blue note labeled 'COMMAND': Represents an instruction or action triggered by a user or system, expressed in imperative form like 'Place Order.'](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/67505ca3234323b5725e1350/68873e05ff23fbbaea3f3ec6_process-modeling-notation.png)

Unlike Big Picture, Process Modeling follows a precise, repeatable pattern:

Event → Policy → Command → System → Event

If the policy requires human intervention, insert:

Policy → [Human] → [Read Model] → Command

This strict flow mirrors how real-world business applications operate and aligns directly with the Software Design level of Event Storming. Capturing processes this way not only clarifies business logic—it also lays the groundwork for system implementation.

Even when Commands seem redundant (repeating the event phrasing), each Command will later map to a specific feature in a system.

As a facilitator, to get the most out of a Process Modelling Event Storming session, it can sometimes be effective to frame it as a collaborative game. The entire group is one team, and the "opponent" is the complexity of the business process itself. The goal isn't to compete with each other, but to work together to map the territory and conquer the problem. The goal is:

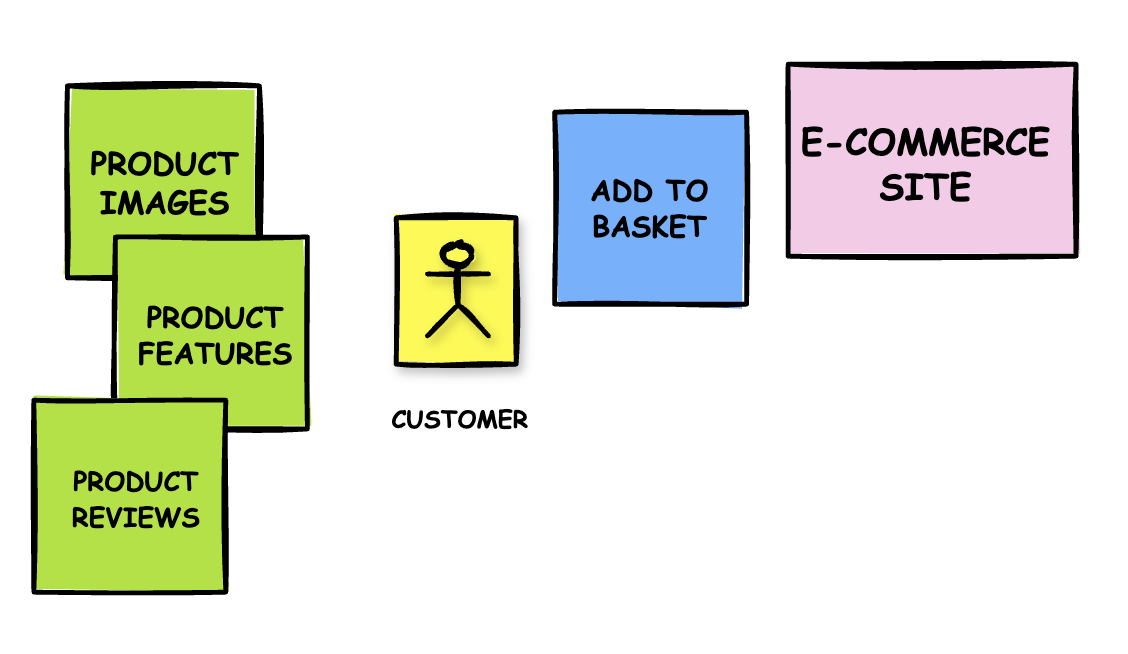

A Read Model specifies the information a user needs to make a decision. For example, before a customer clicks "Add to Basket" for a product on an e-commerce site, they might want to see:

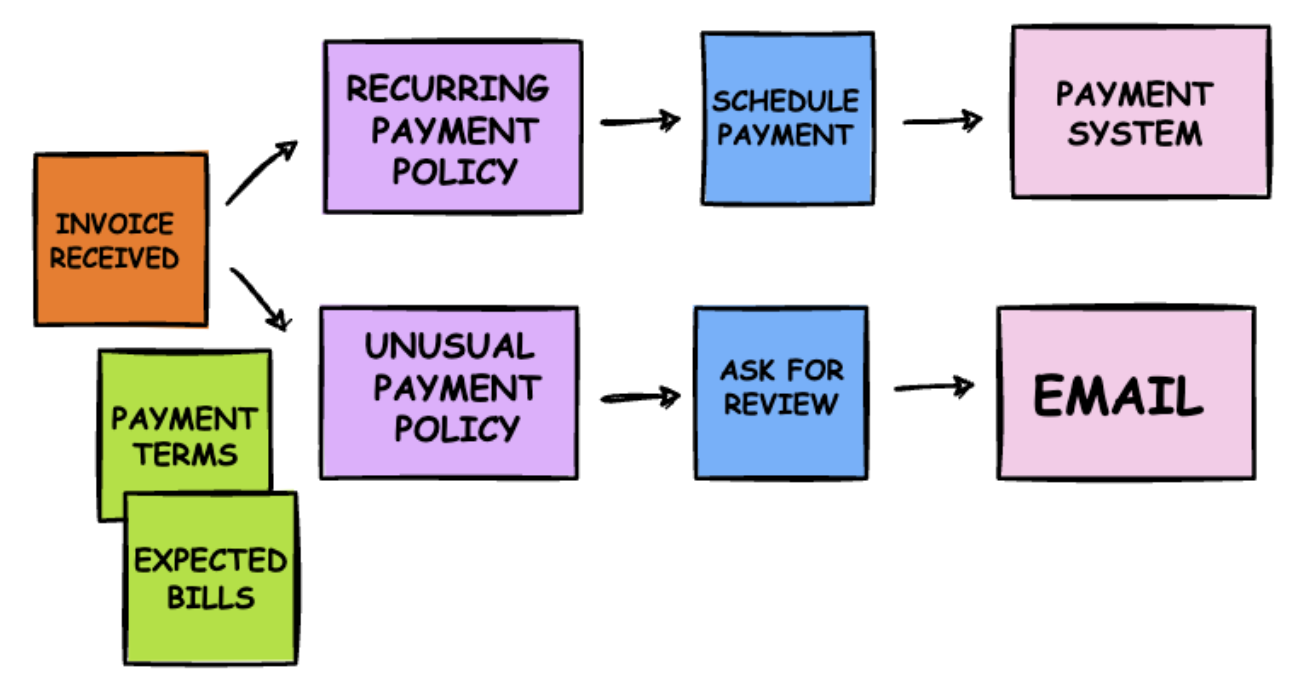

Policies are the lilac-coloured notes that function as the glue between an Event and a subsequent Command. A policy represents a business rule or an automated reaction that is triggered by a specific event.

You can think of a policy as a listener that waits for a certain type of event to occur. The language of a policy often follows a "whenever X, then Y" pattern, using keywords like Whenever, if, then, always and immediately.

For example:

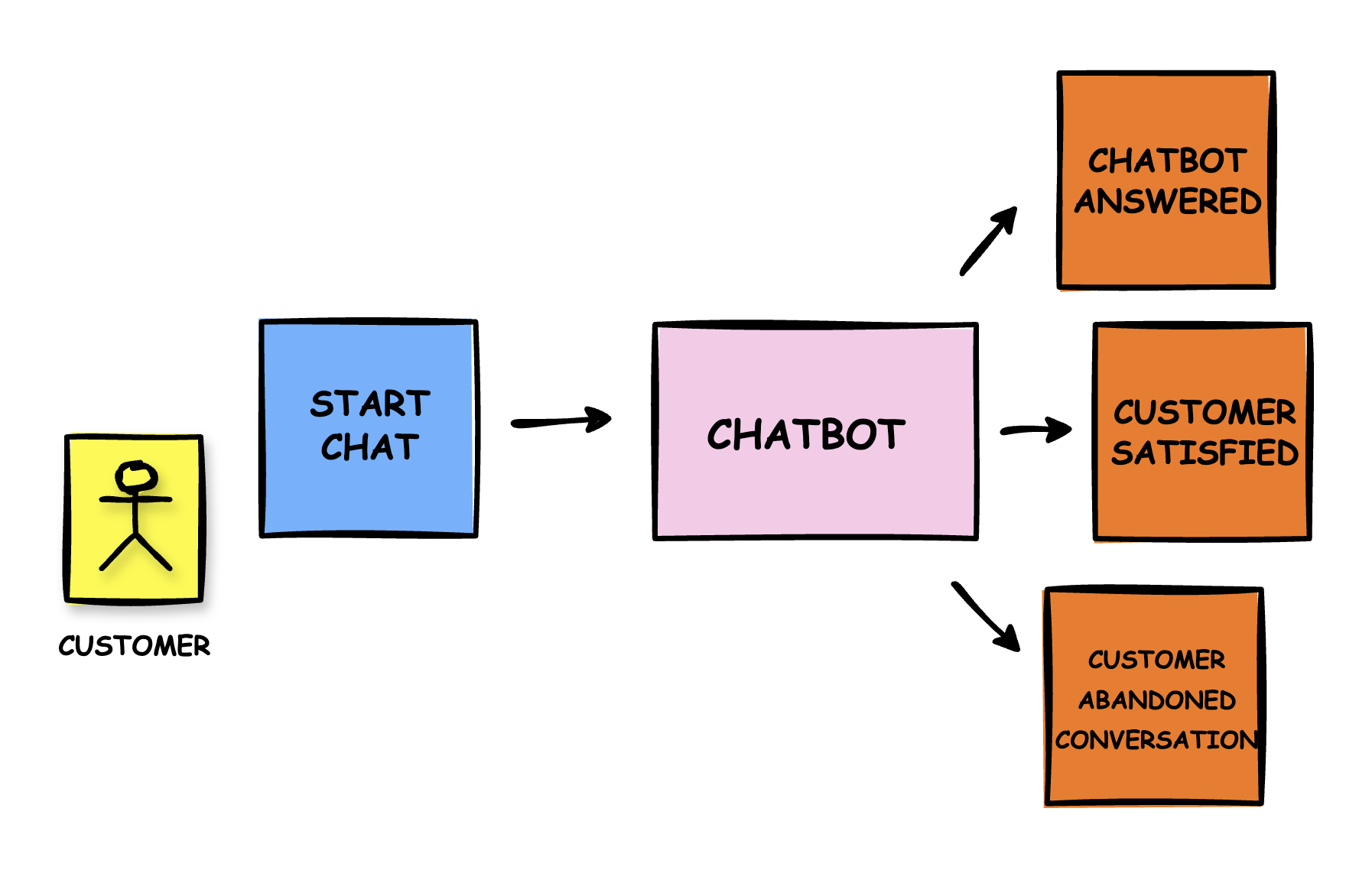

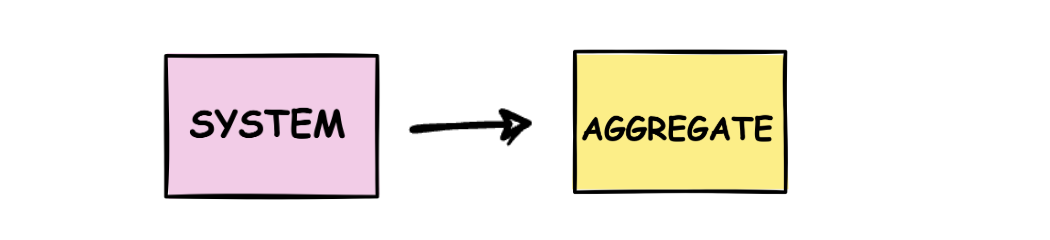

A System (pink sticky note) represents a software service, external party, or internal component treated as a "black box." It receives Commands (blue) and produces Events (orange) in response.

A special case is a Conversational System, like a chatbot or phone call. These are non-linear and better modeled by focusing on the exit conditions (e.g., “Customer Satisfied” or “Customer Abandoned Conversation”) rather than every possible path or utterance. Think of it as a checklist—what needs to happen before the conversation ends?

A Command (blue sticky note) represents an intent to change the system’s state—either from a user or another system. It’s phrased as a clear instruction, typically verb + noun (e.g., Place Order, Cancel Subscription).

Beware of generic verbs like Check, Verify, or Review. These often point to missing Read Models or unclear intent:

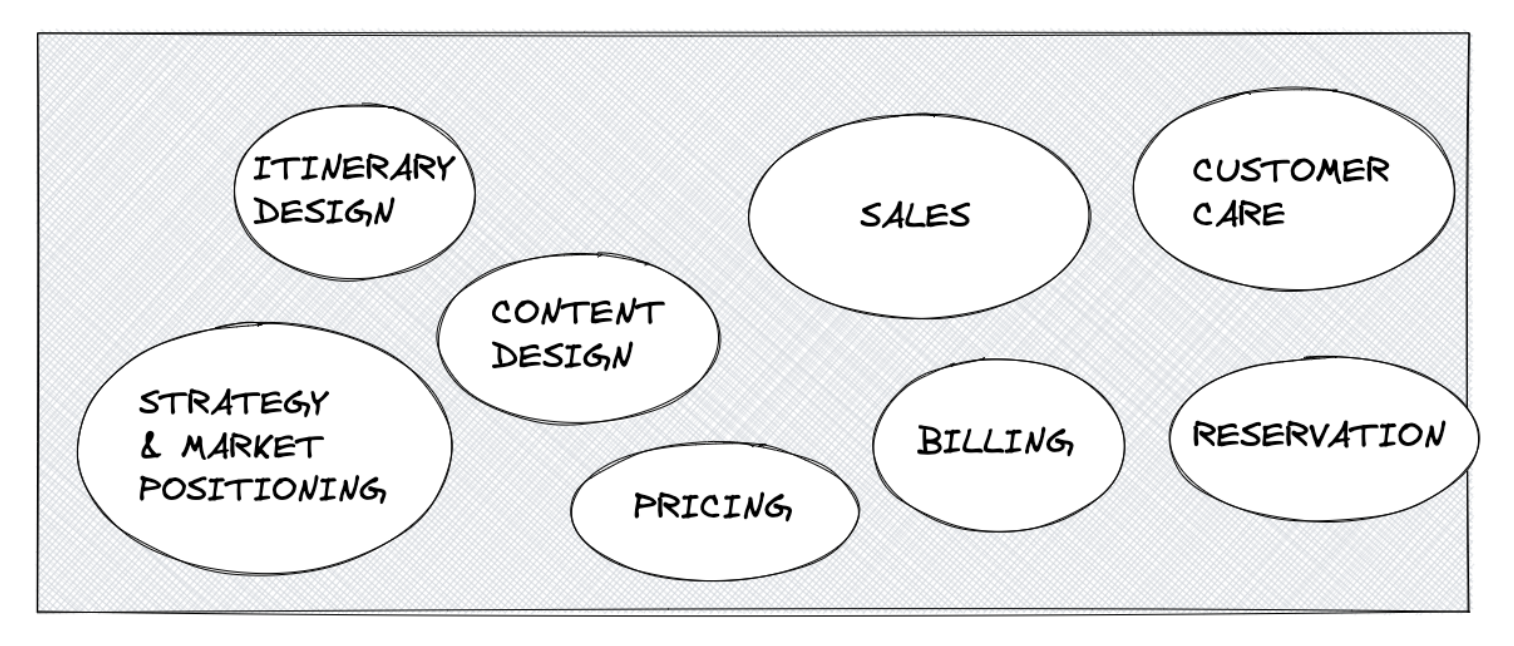

In Domain-Driven Design (DDD), two key goals are identifying Bounded Contexts and Aggregates. These are the foundations for dividing a complex system into meaningful, manageable parts—something notoriously hard to get right. Event Storming offers a hands-on way to achieve this.

One of the biggest challenges in large systems is deciding where to draw the boundaries. DDD recommends using linguistic and organizational borders as guides.

In a Big Picture workshop, these boundaries often reveal themselves. Different departments—sales, accounting, logistics—use different language for similar things. These linguistic mismatches signal where one Bounded Context should end and another should begin.

Forcing everyone into a single unified model creates friction. Instead, let each team work within its own Bounded Context: a system optimized for their language, goals, and expertise.

Each Bounded Context becomes a purpose-built tool for its domain experts—clear, focused, and free from cross-departmental compromises.

Once you've identified a Bounded Context, you can dive into a Software Design Event Storming session focused on that context. This builds on your process model—but shifts the focus from discovery to design.

The main goal:

Distinguish between what you’ll build (core domain) and what you’ll integrate with (generic subdomains).

Here’s how:

This signals a crucial shift:

This small visual change transforms your model from a process map into a blueprint for your system’s architecture.

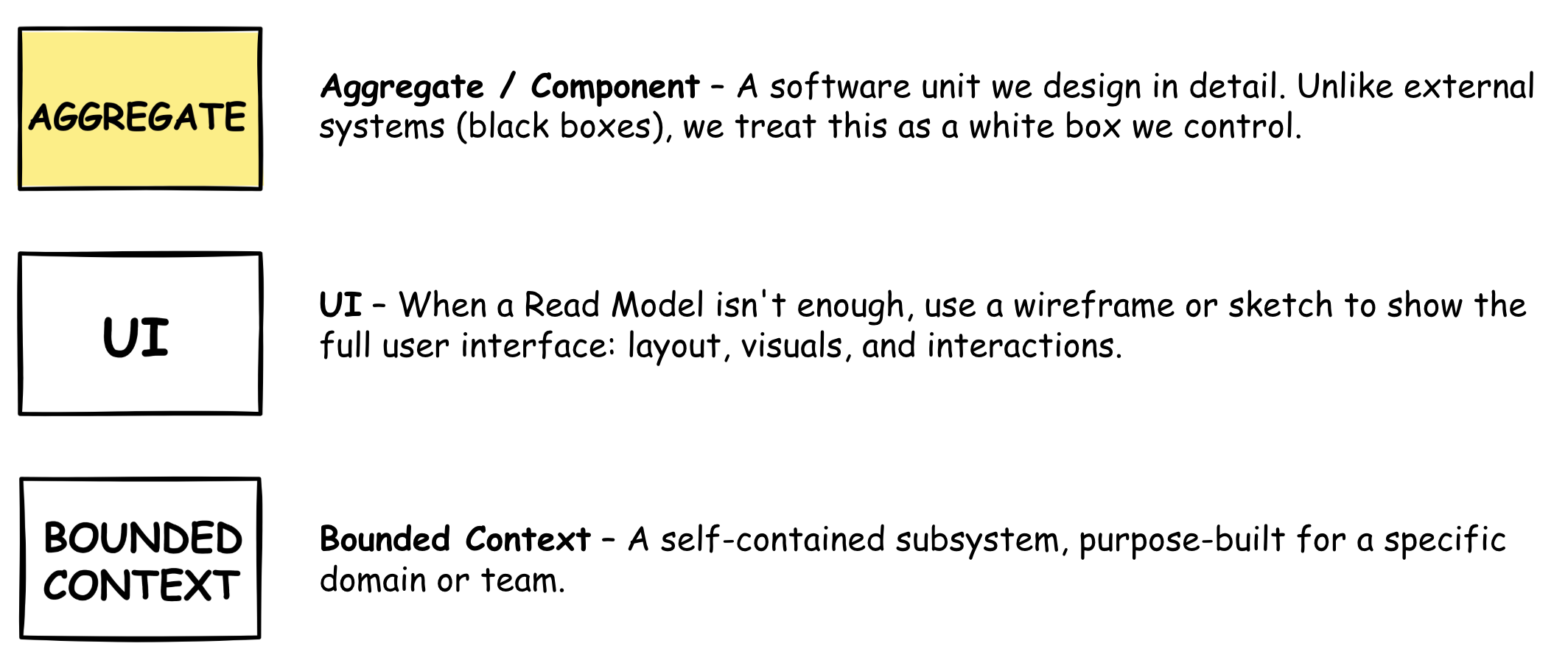

Software Design Event Storming builds on the Process Modeling notation, adding three new elements to support implementation-level thinking:

Our pink System has just been replaced with a light yellow Aggregate.

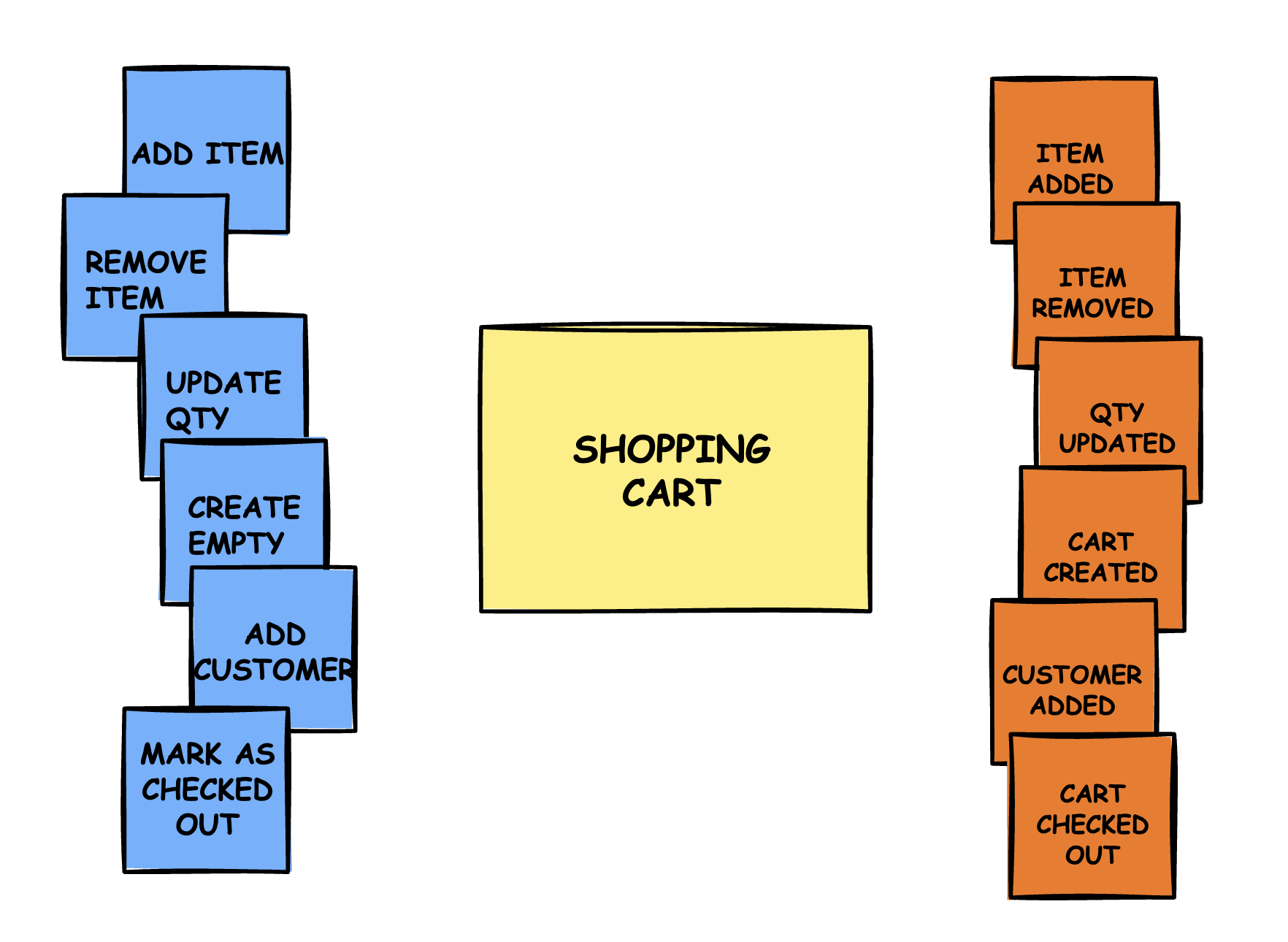

After completing the Software Design Event Storming session, the final step is to shape your Aggregates into well-defined software components with clear responsibilities and boundaries.

This layout visually defines the Aggregate’s public API—what it accepts (Commands) and what it produces (Events)—a core DDD principle.

Once laid out, review each Aggregate for completeness. Missing lifecycle steps are easy to spot. For example:

If you see Update Shipping Address but no Create Order, you’ve likely missed an important starting point in the Aggregate’s lifecycle.

This approach ensures your components are both well-scoped and robust.

If you are looking for a digital tool to help with Event Storming, Qlerify is a purpose-built application designed for this specific workflow.

It aims to solve common challenges in the process. An intelligent drawing engine automatically adjusts the layout as you work, reducing the need for manual rearrangement. For software design, the tool can automatically visualise aggregates by grouping the related commands and events to clarify component boundaries. It also includes AI support that can offer suggestions for process steps, which can be helpful when initiating a session or getting past a block. Sign up for a 4 week free trial.

List of recommended resources: